Why we could see a 127-seat Parliament at the next election

I got told that I "undermine the electoral process" for writing this

Haere rā to the days of 120-seat Parliaments. If Willie Jackson’s comments are any indication, Labour is open to an arrangement with Te Pāti Māori which would cause a major electoral shake-up and lead to a 127-seat Parliament in 2026.

Asked by Q+A’s Jack Tame about Labour’s drubbing in the Māori seats, Jackson says: “What I think our people are saying is that we want Te Pāti Māori and Labour Māori to work together.”

Pushed by Tame about whether this would lead to Labour’s Māori MPs not contesting Māori electorates in future elections, Jackson replied: “I think that the result demands that we look at the future together…how do we best utilise MMP, that’s the question.”

Here’s how a deal might work for 2026. Labour would agree not to actively campaign in the 7 Māori electorates - effectively conceding them to Te Pāti Māori. In exchange, Te Pāti Māori would signal to its supporters to party vote Labour and promise not to go into any coalition with National.

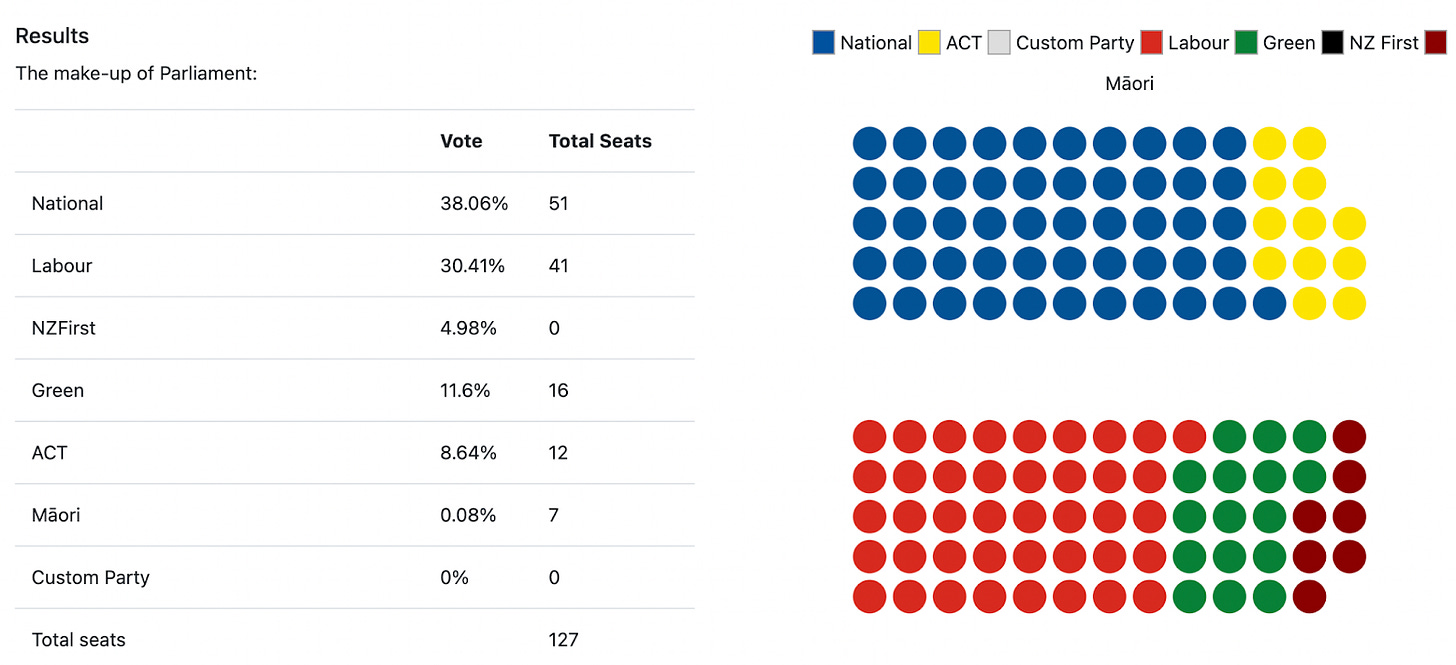

The net result of this would be a seven-seat overhang if Te Pāti Māori’s party vote was less than 0.5 percent. Labour would gain up to 4 seats in Parliament if they received Te Pāti Māori’s 3 percent party vote. If the rest of the results from the 2023 election night were replicated, this would increase the left bloc’s size by 5 seats to 60, and its proportion of seats in Parliament by over 2 percent to 47.2 percent.

Under this scenario and without any other changes, both Labour and Te Pāti Māori would end up with more seats in Parliament. This strategy would also be the most effective way to guarantee significant Māori representation in Parliament. Labour could place its candidates in the Māori electorates high on their list – effectively guaranteeing 14 Māori MPs or 11 percent of a 127-seat Parliament. Māori currently represent 17 percent of the population and will make up a record 27 percent of the incoming Parliament – helped by Te Pāti Māori’s strong performance in the Māori electorates.

This type of electoral agreement relies on voters understanding the advantages of split voting. Māori electorate voters have demonstrated that they understand this better than anywhere else in the country. Te Pāti Māori PM co-leader Rawiri Waititi rode this to victory over incumbent Waiariki Labour MP Tamati Coffey in 2020, arguing that because Coffey would make it into Parliament on Labour’s list, voters would get a ‘two-fer’ by electing him. They obliged, electing Waititi despite Labour pulling in 60 percent of the party vote compared to Te Pāti Māori’s 17 percent. In this year’s election, Labour won the party vote in every single Māori electorate despite losing all but 1 of the seats to Te Pāti Māori. During his interview, Jackson observed that on the campaign trail Māori electorate voters were telling him: “We’re voting for you, we’re just not voting for your candidate.”

University of Otago politics professor Janine Hayward believes that politics in the Māori electorates is different from the rest of the country: “The decisions look different and the discussion and the narrative is very different from the kind of discussion that occurs in the general electorates…what’s interesting to me is how badly the rest of New Zealand understands the politics of Māori electorates.”

Even if Te Pāti Māori’s leaders instructed their voters to party vote Labour, it remains unclear how they would respond. Professor Hayward believes that many of these voters would be unlikely to change their vote for strategic purposes: “They are principled in terms of their decision to be on the Māori roll, and give their party vote to Te Pāti Māori for a whole bunch of different reasons.”

A deal in the Māori electorates alone also wouldn’t be enough for the left bloc to win back power in 2026. Without any further changes, the right bloc - National, ACT and NZ First, would still have a governing majority of 67 seats vs 60 seats for the left bloc of Labour, Greens and Te Pāti Māori.

This completely changes if NZ First fails to make it into Parliament next election. You can’t count Winston out, but based on history you can count on his support dropping after a term in government - NZ First has never increased its party vote after a term in government. At 6.08 percent and without an electorate seat as an anchor, NZ First doesn’t have a lot of room before falling below the 5 percent threshold.

If this happens, we could see a situation where the left bloc is able to win a majority of seats without winning a plurality of the party vote. With Te Pāti Māori’s 3 percent party vote, Labour would only need an additional 0.5 percent party vote for the left to have enough seats to govern.

While the left bloc would have 64 seats to the right’s 63, it would only have 42.1 percent of the party vote compared to the right’s 46.7 percent. This would be an unprecedented outcome but be perfectly within the rules, much like Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 US election despite losing the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes.

Despite the obvious benefits for the left, there are major potential drawbacks that could derail this strategy. Labour might alienate centrist voters by being tied to Te Pāti Māori – the most radical left-wing party in Parliament. Rawiri Waititi has said he’s “not a fan of democracy”, while Te Pāti Māori candidate Heather Te Au-Skipworth has claimed that “Māori genetic makeup is stronger than others.” Labour also risks an internal backlash from former Māori electorate MPs with deep family ties to certain seats, like Rino Tirikatene in Te Tai Tonga.

These MPs can realistically argue that they don’t need an agreement with Te Pāti Māori to win back their electorates. In 2008, Te Pāti Māori won 5/7 of the Māori electorates, but by 2017 Labour had won back every single seat. If Labour is unwilling to properly contest these seats, members like Tirikatene may reconsider their political futures with the party.

There is also an existential risk for Te Pāti Māori that the right would abolish the Māori electorates as political retribution for an electoral agreement with Labour. Both David Seymour and Winston Peters have already called for their dissolution. This type of electoral engineering, and the likely outrage that it would cause, might be enough to convince National to scrap the seats.

Professor Hayward doesn’t think National would agree to this: “I think that would be opening up an issue that no party would want to bring on themselves.” Instead, she believes a deal that significantly increases the size of Parliament is “not going to be terribly popular with voters” and could increase support for electoral reform. An interim report from the Independent Electoral Review Panel in June recommended removing the existing provision for extra seats in Parliament to compensate for overhang seats. The final report is due by the end of November - giving the incoming government an opportunity to eliminate an electoral deal in the Māori electorates that increases the size of Parliament.

The election result is very fresh and a deal like this is only hypothetical. But Labour needs to bounce back quickly - in the 27 years of MMP, no government has been defeated after only one term. If the left is prepared to take the risk, a deal in the Māori electorates would cause one the biggest shake-ups in New Zealand's political history, and perhaps be enough to take Labour back to the 9th floor on MMP’s 30th anniversary.

Substack needs to let me post gifs